Epiphanies and caveats: reading On the Road

How my idea of Jack Kerouac's masterpiece hindered its beauty

Over July, I read Jack Kerouac’s On the Road. “Well, of course you did,” you may respond. At least that, accompanied by a barely-veiled sigh, was the response of two friends when I similarly informed them.

If that wasn’t your reaction, I shall explain.

Published in 1957, On the Road documents Kerouac’s travails and titillations as he criss-crossed the post-World War II United States, encountering orgiastic mountain towns, omniscient vagrants and much feverish “bop”. Written as a continuous scroll during his journeying, the book is part boozed rambling, part travel journalism, part gossip rag.

At its core, however, it is a book about marrow-sucking youth. Countless copies of On the Road will have become dog-eared sitting at the bottom of bursting rucksacks being carted from hostel to hostel by gap-yearing boys.

It has become prescribed reading for young males wrangling with adulthood. I am such a man in his mid-20s, and so my predictable literary choice explains part of my friends’ exasperation. But not all.

Moving in the age’s literary circles, Kerouac offers portraits of the soon-to-be heroes of the “beat” generation; a robed Allen Ginsberg swans around kitchens clutching his poetry, or William S. Burroughs offers his thoughts on the death of the American bar.

Then there is Neal Cassady, the car-thief-turned-rabid-philosopher with whom Kerouac shares a large portion of his adventures, and with whom he is mildly infatuated.

The book’s cultural impact was sharp. It became a central text for the counterculture and hippy movements of the Vietnam War decades, sharing with the rock ‘n roll generation a reverence for sexual exploration, and a taste for mind-altering substances.

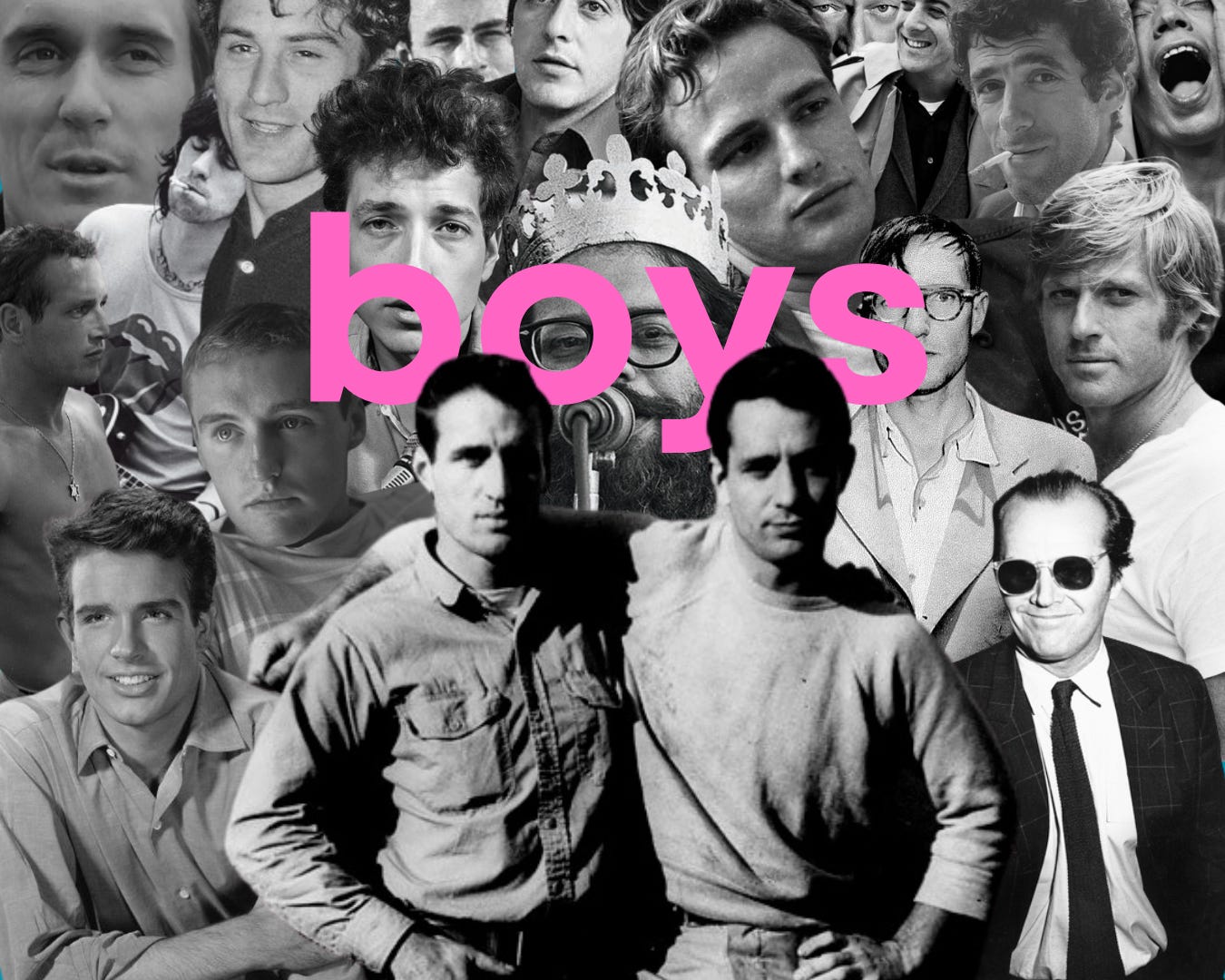

Kerouac, and those he is drawn to, also acted as a template – although not likely the first, and certainly not the only – for the dominant male archetype of the youth culture of the 1960s and ‘70s; the stoic, hard-living, promiscuous, boozy-yet-introspective vision of rugged machismo.

Think Jim Morrison, Keith Richards. Think Cool Hand Luke, Easy Rider. Think Warren Beatty describing his dating life as, “You get hit, but you get fucked a lot.” One can imagine the hip producers in “New Hollywood” discussing the casting for a stripped-back adaptation of the novel, phrases like “Jack Nicholson for Cassady, ya dig” and “Hoffman for Ginsberg if we give him points” wafting amongst the hash smoke.

It’s the masculinity which men often assume is attractive to women, because it is attractive to us. It is stained with chauvinism, and is the second part in the uninspired reaction I received from my two – both female – friends.

I don’t blame them. The exact same connotations of masculinity and unoriginality sprung to my mind when I picked up the novel; I circled with trepidation, wary of the tender but forbidden apple of virility.

And yet, I loved On the Road.

At its core, however, it is a book about marrow-sucking youth. Countless copies of On the Road will have become dog-eared sitting at the bottom of bursting rucksacks being carted from hostel to hostel by gap-yearing boys.

Yes, the aforementioned machismo is present. And yes, by the end Cassady is more redolent of a gurning hanger-on scavenging cigs at an afterparty than the messiah Kerouac worships. But the book is drenched in beauty.

There are the sections which detail the jazz clubs of the era, run-on cocktails of subordinate clauses wrought with such vibrancy as to mirror the music they describe. There is Kerouac’s eye for the minutia of people, and the vastness of nature, describing both with equal and exquisite care, placing them in the context of the gods and cosmos.

Then there is my favourite part, the time they spend at Burroughs’ Texan cabin, a charming detour through “beat” domesticity. The proprietor’s eccentricities – his gun-toting, his disdain for bureaucracy, his belief in solar-replenishment, his heroin addiction – are told with the tenderness of true friendship, a tenderness dotted throughout the novel.

And finally, in stuttering prose, Kerouac sums it all up, the whole goddam mess of it all: “Where go? what do? what for? - - sleep.”

I say again, I loved On the Road.

Yet, when subsequent conversations of what I was reading arose, I added a caveat. Its exact construction varied, but always contained the same sentiment of disapproval, of both the book’s more piggish themes, and my own indulgence in them.

I was warding off the spectre of judgement, burning the sage of self-awareness. But these qualifications were not contained to the public; they bled into the personal. Each moment of intricacy wrenched into existence by Kerouac, each titillating passage I read, was quickly and involuntarily followed by a reminder: “That was good, but the guy’s a bit of a bastard.”

My subconscious insisted on this refrain. Why?

There are the sections which detail the jazz clubs of the era, run-on cocktails of subordinate clauses wrought with such vibrancy as to mirror the music they describe. There is Kerouac’s eye for the minutia of people, and the vastness of nature, describing both with equal and exquisite care, placing them in the context of the gods and cosmos.

Art and culture have always represented people. It is a means of self-actualisation, whether you worship at the altar of Swift and Sheeran, or are, like me, a nauseating hipster. But art is also a means of categorisation. We use it not just to define ourselves, but others.

This trend has (possibly) never been more prominent; Spotify Wrapped, Letterboxd, and X have made sharing our taste easier, solidifying our connection between art and archetypes. This creates a quandary: what if the art you enjoy is associated with people you detest?

Take The Dark Knight. It is a brilliant film, even for the superhero-averse such as myself. However, it becomes difficult to revel in its cinematic majesty when you know the mouth-breather from high school who used to poke fun at your “man tits” recently got a Heath Ledger Joker tattoo on his calf.

Yet I refuse to allow crypto-pedlars and Gillet-wearers to ruin art I love. If I cannot separate myself through taste, I will do so through consumption. “You may like it, but I understand it,” I tell myself. And so I remain removed from – and in my mind at least, above – others.

Hence my semi-detached reading of On the Road. I could not bear to associate myself with the book’s grim manliness, and the flailing, sniffy adolescents who ensure its title is clearly visible to fellow commuters.

I allowed not only the idea of the novel, but also my idea of people who read the novel, to tinge the work itself. I, at least partially, read the book in bad faith.

I’m aware to many this will sound ludicrous. It is a frustrating and crummy habit, and speaks more to my need for art to separate me from others, than it does to any failing of the work. Ironically, it is the exact mentality one would expect from the uppity teenagers I am trying to separate myself from.

Of course the solution is simply not to care, to shake off the imagined societal connotations, to view all art in a vacuum. But I do care, which is not very Jack Kerouac of me. Perhaps that’s the ultimate lesson On the Road was trying to impart. And perhaps, amongst all the caveats, it was the lesson I missed.